A Day in the Life of the Gallatin Stream Teams: Citizen Science in Action

by Tess Parker, Gallatin Watershed Council, and Drew Shafer, Gallatin Local Water Quality District

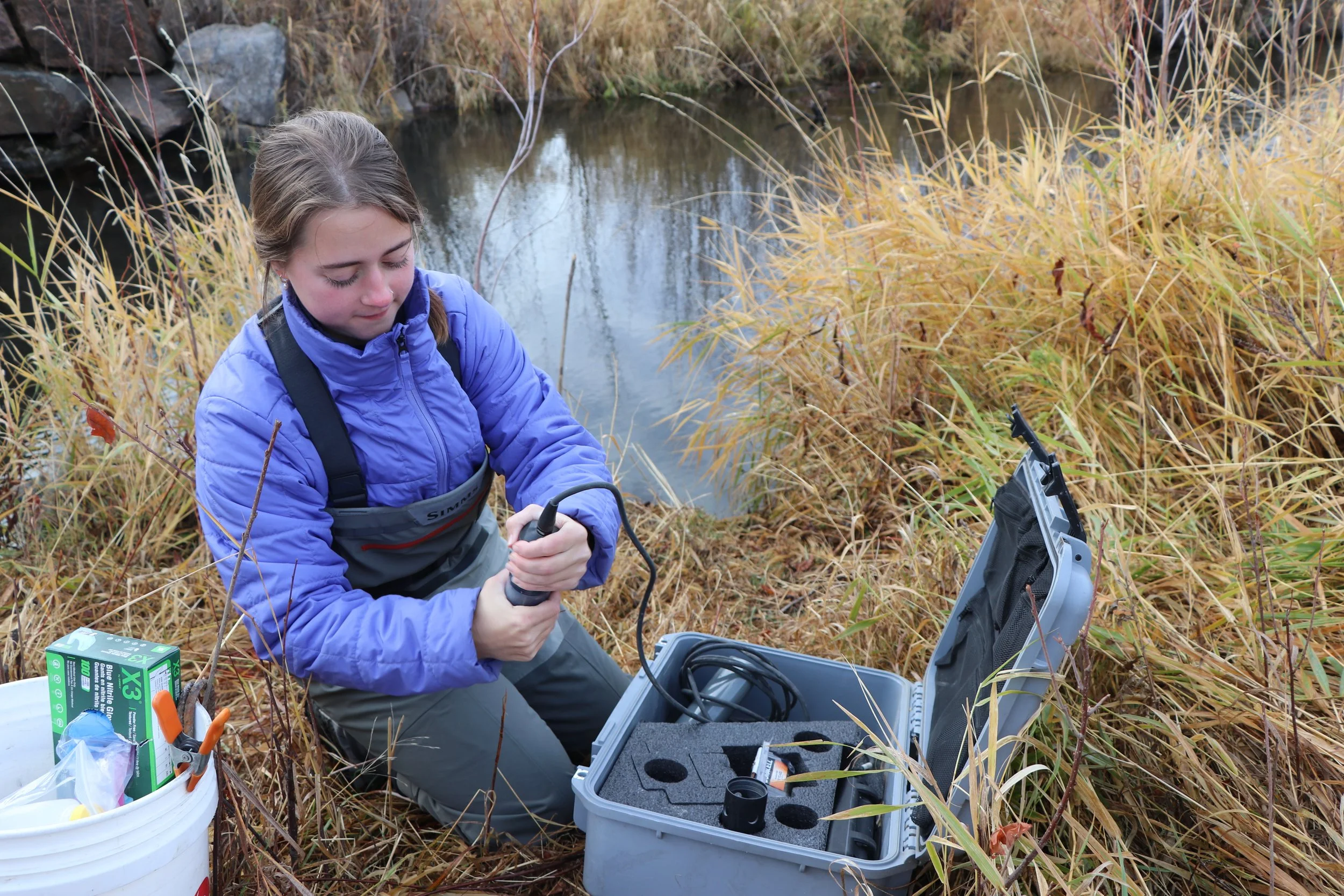

Drew Shafer (GLWQD) assisting Lilian Aizenman (volunteer) with taking a stream flow measurement. Credit: Tess Parker / GWC

Where It All Begins

It's 9:00 a.m. on a chilly October morning, with snow threatening to fall, and Gallatin Stream Teams volunteers are gearing up for a day of stream monitoring. They pack waders, equipment for measuring streamflow and water quality data, a cooler for water samples, lunch, and, most importantly, hot coffee into the truck. Today's crew includes two dedicated volunteers and a Gallatin Local Water Quality District (GLWQD) Water Quality Specialist, ready to visit several sites across the Gallatin Valley.

The rendezvous point may surprise you: downtown Bozeman, Montana. In this area of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, the iconic Gallatin River flows outside town along its 120-mile journey from Yellowstone National Park to its confluence with the Missouri near Three Forks, Montana. This valley is a beloved area for anglers, residents, and conservationists.

Into the River

The first sampling site is on the East Gallatin River, the second-largest river in the Gallatin Valley. The crew moves in a trained sequence to collect water quality data, though with a different type of grace than the trout upstream. The first person gathers water samples for lab analysis, a vital step in assessing the river's health. The second deploys the YSI water quality meter to record key physical and chemical parameters, such as water temperature and dissolved oxygen. The third person operates the FlowTracker, measuring the river's flow rate—called "discharge." Everyone enjoys a friendly wager on the final discharge in cubic feet per second for bragging rights. After checking the staff gauge for water level height (and maybe making a mental note of fishing spots), the team moves to the next site.

From June through October, Gallatin Stream Teams volunteers visit 17 sites during a week of monitoring. These sites reflect the variety of ecosystems within the area. They range from pristine freestone streams to spring-fed channels and even irrigation ditches, covering rural, urban, and agricultural landscapes. Not every monitoring site is out of a Norman MacLean book; some are under low concrete bridges or tucked away in public parks—but all are essential to understanding watershed health.

Voices from the Field

Volunteers like Abby Butler and Lillian Aizenman are the heart of the program. Abby joined to connect with her community and gain hands-on experience with river science. "I valued what the Gallatin Watershed Council and GLWQD were doing and wanted to learn new skills," shared Butler. Aizenman's background in landscape architecture sparked curiosity. "I was interested in being able to be a part of a program that would provide insight into the health of the water quality of the area."

Why Monitor Streams?

Gallatin County has grown rapidly, with the population almost doubling in the past 20 years, according to Census data from 2000 and 2020. Growth brings challenges, particularly concerning nonpoint source pollution (NPS)— pollution that occurs when runoff from rain and snowmelt carries pollutants into rivers, streams, lakes, wetlands, and even groundwater. There is no single point from which the pollution comes; it comes from everyone and everywhere. 90% of Montana’s water pollution comes from nonpoint sources. Examples include urban runoff from parking lots, excess fertilizer, and leaky septic systems. Monitoring efforts like those of the Gallatin Stream Teams are essential to tracking and addressing these issues.

The Big Picture

After a day of wading in rivers and streams, the team ships their samples to a lab for analysis. Meanwhile, Water Quality Specialist Drew Shafer uploads data to publicly available databases. Over the years, this long-term dataset helps track changes across the valley and offers valuable insights for agencies like the Montana Department of Environmental Quality and local decision-makers. The program’s goals include using data to guide restoration projects, inform water management decisions, and foster community stewardship.

The health of our rivers and streams is vital for the ecosystems they support and the communities that rely on them. Programs like the Gallatin Stream Teams demonstrate how local citizens can play an important role in protecting these vital resources. Volunteers learn new skills, collect valuable data, and spend a rewarding day in the water while helping organizations like the Gallatin Watershed Council (GWC) and GLWQD understand the health of Gallatin Valley's waterways. Everyone is responsible for caring for our shared water resources, whether you're interested in fishing, science, the outdoors, or engaging with your community.

Thank you to Simms Fishing for keeping volunteers dry all season and to all those who volunteered with the Gallatin Stream Teams!

About

The Gallatin Stream Teams program is a partnership between GWC and GLWQD. Since 2008, GWC has engaged volunteers in the program, while the GLWQD has provided technical expertise. The Gallatin Watershed Council guides collaborative watershed stewardship in the Gallatin Valley for a healthy and productive landscape. The nonprofit supports the sustainability and health of the Lower Gallatin Watershed through collaborative partnerships, community education, restoration efforts, and individual empowerment. The Gallatin Local Water Quality District focuses on water resources education and water quality monitoring for increased awareness of water-related issues and public health. It is guided by its mission to protect, preserve, and improve groundwater and surface water quality within the district.

Snapshots from Sampling

Pictured: Drew Shafer, GLWQD, Abby Butler, volunteer, Lillian Aizenman, volunteer. Photo credit: Tess Parker / GWC. Map: Madeline Minutelli / GLWQD